A SLOW RECOVERY FOR TITLOW ESTUARY

What nature took millions of years to create took man only 100 years to greatly alter a precious ecosystem that local efforts hope to restore in Tacoma over the next 10 to 15 years.

What nature took millions of years to create took man only 100 years to greatly alter a precious ecosystem that local efforts hope to restore in Tacoma over the next 10 to 15 years.

In another step in recovering natural habitat and improve local watersheds, the Washington State Salmon Recovery Funding Board awarded a $150,000 grant in December to assist in design and initial planning permits for the restoration of the “Titlow Estuary” in Tacoma.

Known to many as the “duck pond” at Tacoma’s Titlow Park, it was once a self-sustaining tidal embayment that teemed with trout and migrating salmon in the lagoon and connected creeks draining into the shoreline along the Tacoma Narrows in Puget Sound.

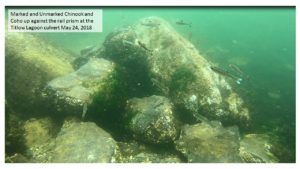

However, the railroad mostly filled the narrow passage into the small inlet in 1911 when they placed tracks that run within feet along the Puget Sound shoreline, leaving only a 3-foot culvert to drain fresh water running that flows into the lagoon, but blocked fish migration and most the natural tidal action.

However, the railroad mostly filled the narrow passage into the small inlet in 1911 when they placed tracks that run within feet along the Puget Sound shoreline, leaving only a 3-foot culvert to drain fresh water running that flows into the lagoon, but blocked fish migration and most the natural tidal action.

And in the 1950’s it was sealed on occasion to create a public “swimming pool” that resulted in an overabundance of waterfowl, more algae, and conditions that eliminated most salmon and trout species there.

“Though unsuitable now, the estuary can be restored with proper planning and funds,” said Kristin Williamson, a Salmon Restoration Biologist with the Sound Puget Sound Salmon Enhancement Group (SPSSEG) that was awarded the grant to develop designs and permits to restore the natural salt marsh estuary and improve water quality.

As part of the grant, SPSSEG will coordinate with the City of Tacoma and Tacoma Metropolitan Park District that will also contribute $27,000 additional to the effort to develop plans to replace the fish-blocking culvert with multiple rail and pedestrian bridges.

As part of the grant, SPSSEG will coordinate with the City of Tacoma and Tacoma Metropolitan Park District that will also contribute $27,000 additional to the effort to develop plans to replace the fish-blocking culvert with multiple rail and pedestrian bridges.

“This is a good step, but it is a long-term process before it is completed,” Williamson explained of the “process” that can take 10 to 20 years by the time final designs, costs, permits and funds to complete the project.

Final cost to restore the Titlow Estuary, could cost anywhere between $3-Million to $10-Million or more, depending on the scope of the project, which now calls to replace the 3-foot by 102-foot long culvert with a 96-foot rail span bridge, remove fill and park infrastructure from the lagoon edges to increase the lagoon size.

Plans also call to work with the City of Tacoma to improve water quality through green infrastructure and storm water treatment. Sidewalks, trails and public areas would also be improved.

Plans also call to work with the City of Tacoma to improve water quality through green infrastructure and storm water treatment. Sidewalks, trails and public areas would also be improved.

At the point final designs and permits are finalized, the more critical issues will be funding available at the time and most likely involve both the Transportation Department as well as the Railroad.

“That’s why it takes so long before we see the results of our work,” Williamson explained of her efforts as project manager and fish biologist on restoration projects focused in the Pierce County for SPSSEG.

Though it may take a decade or two before a specific project comes to fruition, Williams said “direction is heading in the right direction” as far as funding and awareness of environmental issues, water resources, and recovery of natural habitat.

For example, the State Salmon Funding Recovery Funding Board was created under the Washington Recreation and Conservation Office in 1999 to specifically recover and restore dwindling salmon resources.

And, in the just the past 20 years the Recreation and Conservation Office estimates the Funding Board has awarded 3,093 grants and surpassed the $1 billion investment in the past 20 years to: correct 713 barriers to migrating fish, giving salmon access to 2,082 miles of habitat; conserved 537 miles of streams; restored more than 48,500 acres of shorelines, estuaries, wetlands, and other stream habitat; and more than 17,700 acres of land along rivers, wetlands, and estuaries have been cleared of invasive species.

“Most the time the culverts and pipes that carry streams under roads and railways often block fish migration because they are too small or too steep for fish to swim through easily,” Williamson explained of structures constructed 50 to 100 years old, many failing.

Besides removing barriers to migrating fish, significant funds are also spent to purchase and restore shorelines and wetlands.

For 2019, the Salmon Funding Board awarded $26.1-million in grants, including $1,176,613 in Pierce County for: a preliminary design to remove the Cambers Creek Dam on Chambers Creek between Lakewood and University Place; funds to buy 33.6 acres along South Prairie Creek; buy 11.4 acres in the Lackamas Flats; buy 33.6 acres along Ohop Creek; correct two barriers in Horn Creek; buy land in Pacific Pointbar on the White River in Sumner; and plans to restore the Titlow Estuary.

“Of course, there is never enough funding, but we are making good progress as compared to 50 years or even 30 years ago,” Williamson said before serious efforts began to restore and recovery natural habitat.

A big part in those efforts came in 1990 when the state created 14 Regional Enhancement Groups (RFEGs), including the SPSSEG to specifically work with local, state, federal agencies, Native American Tribes, citizen groups and landowners in salmon recovery efforts

The SPSSEG service area includes six Water Resource Inventory Areas (WRIA’s), or watersheds as defined by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and generally includes Pierce, Thurston, and Mason counties.